Recent Additions to the Flinders University Art Museum Collection

Flinders University City Gallery, State Library of South Australia

8 May to 19 July 2009

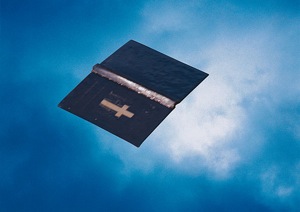

The shimmering Bible floating in the big sky of Michael Riley’s Untitled (Bible) (2006) from his Cloud (2000) series is gently seductive and subtly subversive. The Bible floating upside down, pages open and detached from institutional power doesn’t seem quite itself. On its own, it is leached of power and it is the numinous blue sky that represents place, spiritual presence and force, shifting and evolving beyond the range of symbols and forces imposed on it. At the Festival last year, the whole series of Cloud was shown as a continuous banner above North Terrace. At home in the sky, Bible, boomerang, angels, locust and a cow, floated, pierced by light an elegant and profoundly rich and moving storytelling.

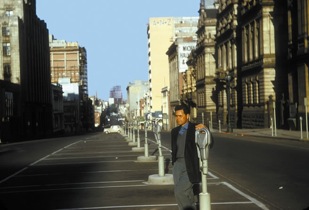

As the autumn light here carves the city up into so many pieces of yellowish cake, the soft light that falls down the hill of the unknown city street in Brenda L Croft’s Man About Town (2003) is familiar but dislocating. A well dressed man stands alone in the city street, unstaged, this is an actual image of Croft’s father in this unidentified time and place. Like a film still it suggests unlimited possible narratives yet offers an image of Indigenous life of that time outside the accepted national imaginary, both unsettling this history and making it more mutable and complex.

Jonathan Jones embossed prints White Poles 1-3 (2004) with their shadow play of clattering, falling diagonals creates a subtle dimensionality. As the viewer moves around the prints, it seems that the interlocking mesh of lines will open out into a 3d space that one can move into and through. Jone’s work explicitly draws on the fluid lines of Tony Tuckson’s White Lines on Ultramarine (1970-1973) which was in turn a refinement of Yirrkala work collected by Tuckson and Johnson simultaneously pays homage to Pollock’s Blue Poles (1952). Working fluidly in both western and indigenous traditions, Jones’ subtle image of light and spatiality effortlessly connects these traditions.

The repetitive whorled forms of Dennis Nona’s stunning lino print Ara: Boxing Waves (2006) flow and change across the large scale print becoming the unweaving story of the sea, the reef and the sea turtles that hide from the hunter under the “boxing waves”. The dense patterning embodies the currents and dazzle of the sea and the richness of these forms and transmission of cultural knowledge.

All artists here play with light, as medium, as idea, it’s here in the refined shadow movement of Jonathan Jones’s prints and in the photographic gloss and complex codes of Foley and Siwes work, it’s here too in the plate tone of Terry Ngamandra Wilson’s beautifully spare etchings Waterholes at Barlparnarra(2007) and Gulach (2007) and in the fiery eyes of Nora Rupert’s’ spirit beings in Mamu(2003). As down a city street, light connects and reveals, illuminating and re framing what was thought familiar.

Jemima Kemp

Published

May-June 2009

Comments (0)