Simryn Gill

Samstag Museum

7 August to 30 October 2009

Felicity and serendipity are words that seem now only to be used by those who imagine themselves in Jane Austen mode. Embracing the role of fortune and chance, perhaps they are inimical to the narratives of control that culture cultivates. It was the Serendip Princes who continually discovered things that “they were not in quest of” and found felicity or good fortune in the unlooked for discovery.

Fortune and chance rub up against each other in these words as they do in the work of Simryn Gill, her fascinating collections of objects embodying the interconnected complexity of the world, the act of collecting as sustained enquiry and the faith of the collector in giving over to chance, serendipity and good fortune.

The collections in Gathering are loose, changeable things that feel very much like things that have come to her or been dis-covered rather than actively sought. Garland(2006) is an enticing pile of detritus picked up from Malayan beaches that immediately activates the scavenger urge to pick through it. Loosely arranged there seem to be categories; green (malachite, plastic), black (iron nails), the terracotta of roof tile shards and the blue and white of pottery but there is more confusion here than appears; organic looking metal, the shell like plastic of a fragment of false teeth, to classify seems impossible yet this threatened confusion strengthens this urge to sort things out, to lay bare the connections between things and Garland is absolutely engrossing.

Garland subtly alerts us to the central process of Gill’s work as in both meanings of the phrase, she thinks through things and it is through objects that her art engages with the world. Her collections are both material and process as she uses the world of objects to make sense of ideas, propositions and historical political circumstances. Propinquity too then is another less used idea that sits alongside serendipity and felicity in Gill’s work as these collections through chance and their gathering together uncover affinities and reveal the relations between things as the spaces where meaning resides.

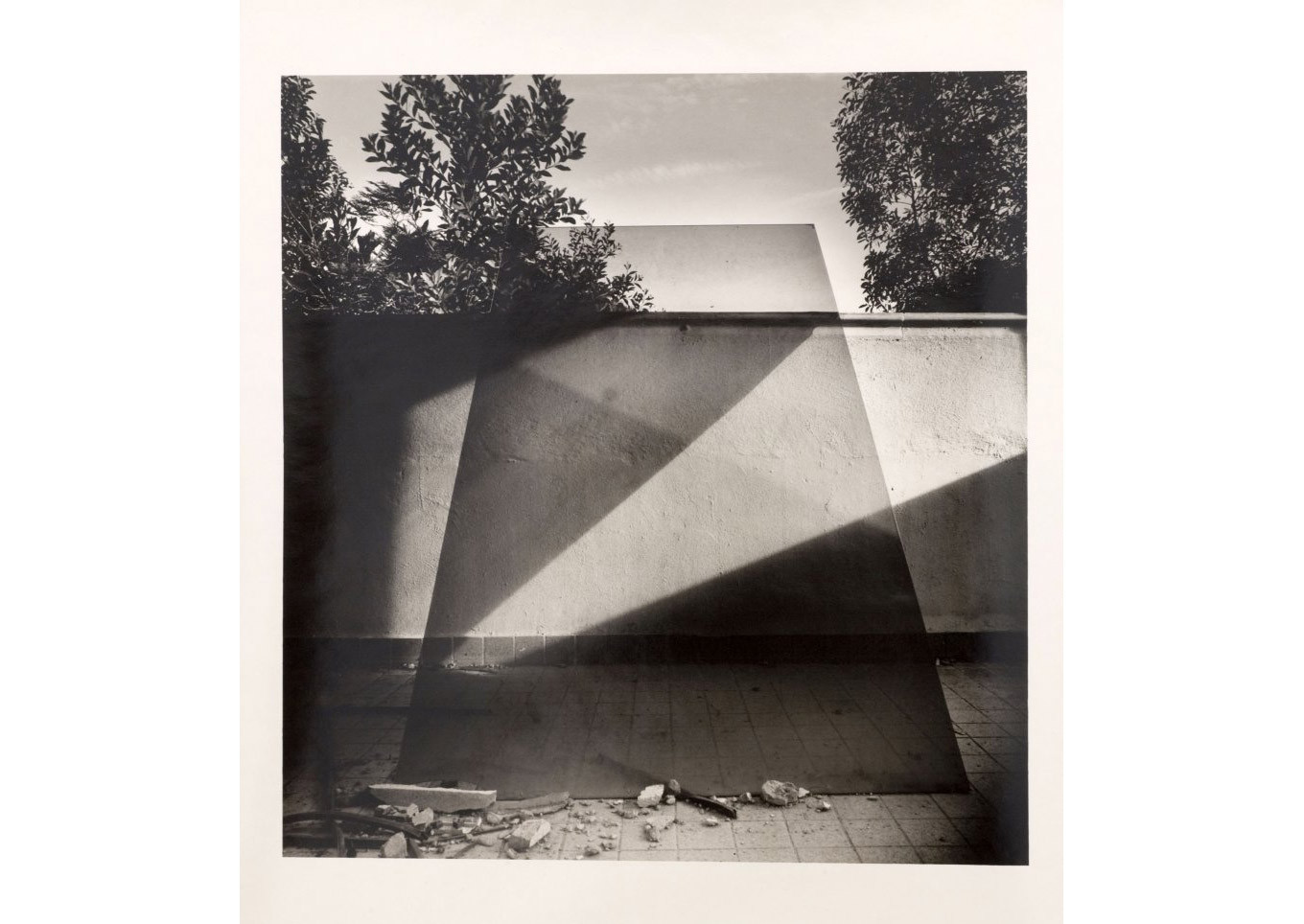

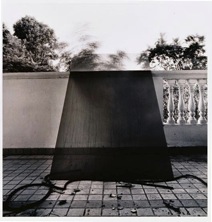

The serendipity of economic necessity illuminates the extension of Colonial pasts into the present in My Own Private Angkor (2007) a series of photographs showing slabs of smoked glass leaning against the walls of decaying rooms. The title refers to the European “discovery” of Angkor Wat in the 19th century and invokes Orientalist myths of “lost’ cities and encroaching jungles but the formalist arrangements of the glass slabs removed from the more valuable aluminium frames and left in these houses is the product of economic trouble traceable back to colonial pasts. The European myths of Asia and the lost futures of these rooms seem linked in the liminal spaces of the window voids. Glass removed for economic gain it seems that their abandoned futures are an continuation of the colonial mythological past.

The relations between inside and out are embodied and transformed in Untitled Interiors (2008) a series of bronze casts of drought fissures, cast by a traditional Thai maker of sacred objects, Interiors embodies these physical relations of space, (the place of the cast and the maker) and the social relations spanning Australia and Thailand of their making, locating them as multi layered objects within this net of relations, time and place as surely as the collection of footpath crayon rubbings, Sydney Maps (1998) places the artist in that exact moment and location.

Upstairs is the Reading Room, a collection of collections not so much to illustrate Gill’s processes but to draw attention to what is shown in public and what is excised, how collections are formed not only by serendipity but intent and design. Here is some of her most intimate and affecting work, a pile of mango stones sucked by friends and then cast in tin, that ephemeral action and relationship solidified (Some of my best friends suck mangoes 1998), the transformation of loved books into ritualistic beads in Pearls (1999) recalling the mourning beads of New Guinea. Gill talks about her work being deployed into the world and coming back, this circulation of things transformed is that of the gift moving from hand to hand, an engagement not only between maker and recipient but drawing others into its circuit of generosity. This gathering from the world and giving back marks her deep faith in and engagement with it, with locating oneself in it, with sorting the world out but also giving up to chance, being open to felicity and serendipity.

For Paper Boats (2009) Gill invites viewers to make boats from pages of the Encyclopaedia Britannica 1968, transforming knowledge and playing with its authority. Making my own boat and letting the encyclopaedia open where it would, I got “Hungary”, turning over my finished boat to place it in the flotilla slewing across the floor, it revealed to me its name, “Hunger and Thirst”. Serendipity indeed.

Jemima Kemp

Published db Magazine

September 2009

Comments (0)