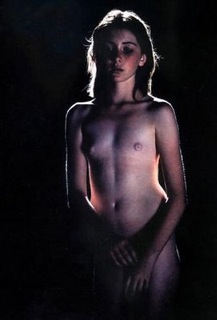

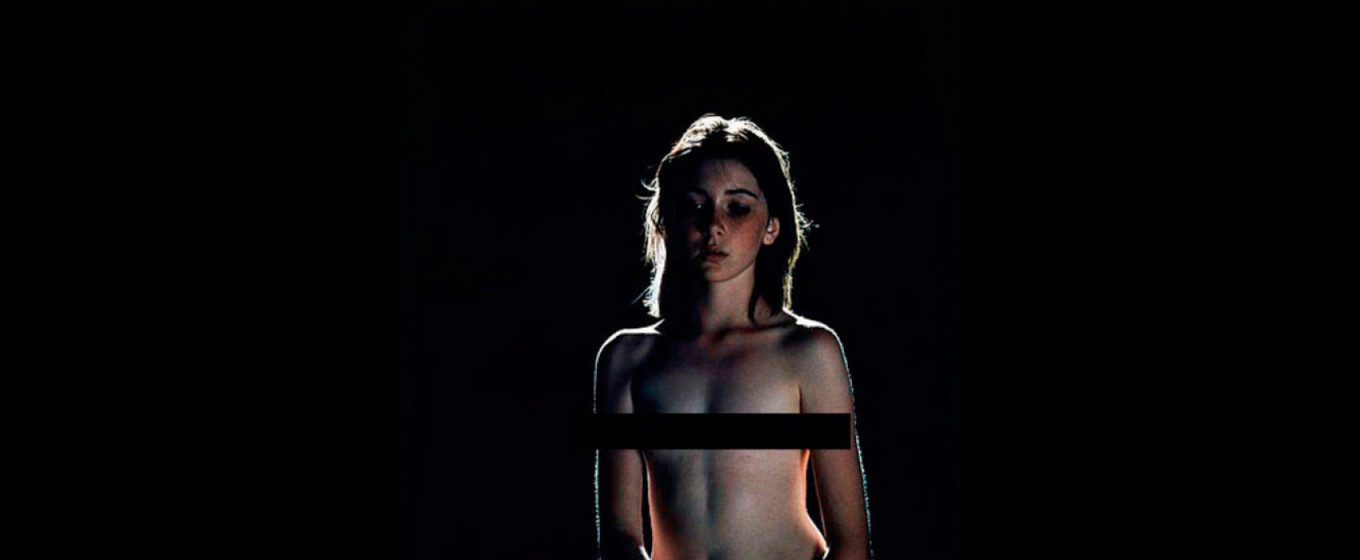

Image above censored by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation

WHEN WORLDS COLLIDE…

The politics of moral panic

Bill Henson, nude, untitled, 2008

Image © The Artist

The moral panic surrounding the Bill Henson photographs seized in May 2008 has served to highlight if not elucidate a knot of issues and ideas about the rights and freedoms of artists to make the images as they choose and the rights of “the public” or the Government on its behalf to limit this freedom. Further and crucially there is a nebulous bundle of concerns, ideas and beliefs at its core about the use, control and interpretation of images.

The Federal Government’s quick response to the Henson panic was to charge the Australia Council with the development of a protocol regulating the depiction of children in the visual arts. The keyword that has raised concerns that this will turn out to be a form of state control over art and artists is the use of “depiction”, in that it seems to relate specifically to the content of image.

The four key issues that comment was invited on are:

• Ensuring that the rights of children are protected throughout the artistic process – from the time an artwork is created through to when it is shown.

• Ensuring that everyone viewing the artwork has an appropriate understanding of the nature and artistic content of the material

• Protecting images of children from being exploited, including use of the images beyond the original context of the creative work

• Creating protocols that acknowledge the Australia Council’s statutory role in upholding and promoting the right of people to freedom in the practice of the arts.

An Australia Council spokesperson advised that these four issues were developed by the Council in response to the request from the Minister, Peter Garrett and that 45 submissions were received. The press release stated that “key stakeholders” would be consulted in this process, in response to my enquiry as to whom the “key stakeholders” were, the Australia Council advised that initial consultation with these parties was conducted in confidence and that they were not able to identify them. It may be illuminating to see if, in the draft protocol due to be released for public comment in mid November 2008, these groups are identified.

It appears that Australia may be unique in developing a protocol that seems to seek to control the creation, interpretation and use of images and in making this a funding condition. The Arts Council (England) has guidelines for working with children, the disabled and vulnerable persons but these do not involve the content or use of images the Scottish Arts Council appears to have no funding conditions tied to working with or the depiction of children in art, American National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) grants are subject to relevant Federal and State laws (anti discrimination etc.) but has no specific grant conditions tied to either depiction, creating contextual understanding or protecting the use of images.

Even given that the protocol has not been drafted, these four points raise some immediate issues:

1. Is it properly the work of an arts funding body to protect the rights of children and to develop a protocol specifically to this end, where State and Federal laws and bodies already exist? How is this to be enforced?

2. This raises the prospect of warnings and proscriptive interpretations of a work. What is, whose is “an appropriate” understanding? And where does this leave ambiguity and mystery in art, the subjectivity of our individual relations with art is undeniable.

Warnings sound innocuous but imagine coming to Romeo and Juliet for the first time and receiving a warning that “This play contains underage sex, violence, suicide”. Frank Moorhouse, who has been outspoken on this issue, points out that as well as all of that, Juliet is 13, he writes “Classification robs art of its power to shock and surprise and to offend” as well as reinforcing “a genteel view of language and art” and carrying ‘”implied moral prohibitions about the acceptability of realism and truth”.

3. This may in fact only refer to or prevent an artist re-purposing an image at a later time that takes it out of the context of the original work. However, this statement is both broad and ambiguous and can be interpreted as referring to the control of the reproduction and use of images. If this interpretation is codified in the draft protocol, this would seem to be the most problematic in terms of enforcement, whose responsibility it would be and how this could be policed. While there are controls and boundaries on the legal reproduction of images, the illegal and personal use of images is effectively uncontrollable.

Researching this article I came across a news report where Victoria’s Child Safety Commissioner as part of a submission to the Senate Enquiry into the Sexualisation of Children in the Media stated that he had been advised by professionals working with (sex) offenders, of their clients “interest in, and use of, sexualised images of children within advertising and marketing” including children’s clothing catalogues such as are delivered free to homes. This would seem to indicate both the impossibility of controlling the end use to which images can be put and that imposing protocols on the visual arts only ignores the main media game with its proliferation and easy availability of images of any kind.

4. Frank Moorhouse again “This demand for protocols is not about protecting children: it is about controlling art. It is an expression of misunderstanding of the nature of art in a Western society and an ideological distrust of art and an ill-considered reaction to moral panic.”

In his 2008 Coombs lecture Imagination in the 21st Century, he writes further “Traditionally in Australia we have argued — and generally achieved — funding decisions should be made on evidence of talent and the assessment of the originality of the project regardless of political or religious or personal beliefs or affiliations or ‘character’ of the artist and without regard to any reductive analysis of content.” How then, can it be argued that the possible proliferation of protocols that seek to impose proscriptive controls “acknowledge the Australia Council’s statutory role in upholding and promoting the right of people to freedom in the practice of the arts”.

Given that the Australian Bureau of Statistics estimates that there are around 281,000 visual artists who receive payment for their work, and the Australia Council gives out 50 emerging artists grants per year, the real danger doesn’t seem to lie in artists tailoring their work to comply with grant conditions or that the practice of artists like Henson will be effected as Henson hasn’t needed to receive public funding for some time.

Rather the risks are that other funding bodies choose to apply similar guidelines or protocols, that festivals, exhibitions and performances increasingly feel pressured to advise, warn and offer “appropriate” interpretations, that galleries and corporate sponsors shy away from anything with a whiff of danger and that artists themselves begin to internalise these prohibitions and self censor their work. That in fact, it is the elements of risk, surprise, danger and the ability to make and experience art that disturbs, sometimes shocks but questions and reveals that are at risk.

Henson’s images have sometimes made me uneasy yet I would rather have the opportunity to be presented with them and to think myself about what it is that has produced this uneasiness yet also lets me find them profoundly beautiful than to have this experience diluted, degraded or prohibited.

Point Blank Issue.04 November 2008

Comments (0)