Art Gallery of South Australia, until 26 January 2010

For iconic status, John Brack’s Collins Street, 5pm (1955) is right up there. It’s trudging queues of commuters that echo the lines of the buildings, the restrained palette that seems so Melburnian, (which came first, Melbourne’s love of the sombre or Brack?) the seeming joylessness of it all.

But while Collins Street has become a shorthand for the urban grind and Brack typified as the quintessential painter of urban life, for icons to operate the original has to become a kind of code abstracted from the circumstances, the flesh of its creation. To look at it only as an icon and Brack as a painter of icons misses almost entirely the range and the humanistic curiosity that drove his life’s work and wove it into an continuing enquiry into humanity, the what and how it is to live.

Moving through this large retrospective, it’s clear that Brack was a careful shepherd, his finished output isn’t prodigious and there aren’t the mounds of preparatory work that artists like Nolan left behind. This care for the structure and the finish, that the work might be read how it was made, pervades each painting. It’s a meticulous care that is there in the coolness of his work, in the attention to the interactions of line, form and colour, the careful arrangement of forms within the picture space and there too in the fineness of his observation.

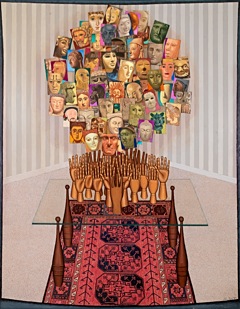

Image: John Brack (1920-99)

The Hands and the Faces (1987) oil on canvas 213.1 x 167.5 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program, 2009 © Helen Brack

Brack has been accused, then and now of being a callous observer and his works, with their hard edged graphic style simply cartoons of life but his capture of the telling detail; the lines of a face that mimic a mannequin inWoman and Dummy (1954) the wary eye of a child in The Baby Drinking (1955) the lines of rooftops in North Balwyn Tram Terminus(1954) that are repeated in the silhouettes of the drinkers hats in The Bar (1954) are distilled observation that spring from a deep empathy. Details are used, not for the cartoon’s punch line but in setting up relations and affinities between things, hats and suburbs, animate and inanimate, to continually worry away at the edges of the big and small questions of human existence.

If Brack had a manifesto, it is a letter to the then director of the NGV after it’s acquisition of Collins Street when he wrote that “If I choose to paint the life I see around me, it is because I find people more interesting than things. On the other hand, one cannot, since Cezanne, be casual about the structure of the picture.” Here it is then, the dynamic balance between the structure of the pictures, the rigour of control over the palette, the deliberate dynamism of forms and lines within the frame and the curiosity about humanity that propelled the work.

Balanced against the tension between picture making and his ever present curiosity, Brack’s work is always refracted through art invoking other meanings, inflecting his work, The Bar(1954) a homage to Manet’s A Bar at the Folies Bergere (1884) except that, unlike Manet’s barmaid who avoids the eye of her would be suitor, the stance and smile of Brack’s barmaid shows that here, in this limited domain, she is in control.

So too, The New House (1953) while lacking the shimmering languor of Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1884) might be seen as part of the same continuum. Seurat showed the newly prosperous bourgeoisie as they wanted to be seen, as people wealthy enough for leisure, Brack shows the new home owners as they wish the world to see them in the fulfilment of their own bourgeois dream. His series of exceptionally fine pen and ink drawings and etchings of jockeys racing descends directly from Toulouse-Lautrec except that the massed black bulk of his racegoers and grim jockeys have none of the fluid lightness of Lautrec’s. Similarly, Brack has revoked the facile eroticism of the original in The Boucher Nude (1957), forcing the viewer to look again at the body naked rather than nude.

His work might be seen as a continual refinement, a stripping away to the bones of the thing but always expressed through these complex codes. Pencils take the place of people and soldiers in The Battle (1981-3), social distinctions maintained between pencils and their mechanical ilk as they swarm across the table top. Later they carry scrabble letters spelling out alliances in We, Us, Them (1983).

Brack’s last paintings are tableaux of hands and postcards, all of civilisation, kings and queens refined into image. In The Hands and the Faces (1987), this panoply of

civilisation rests unsteadily on glass balanced on gymnasts clubs over a blood red Persian rug. Not quite a vanitas but all the grand themes, civilisation’s growth and collapse, love, spirituality, power and its discontents, beauty and death, history distilled into a fan deck, fragile and contingent.

Held always at this point of tension, of things about to move, fall or slip out of reach, and always aware of arts artifice Brack’s work continues to resonate and intrigue in reminding us that things are never what they seem.

Jemima Kemp

Published dB Magazine

December 2009

Comments (0)