Japanese Art from Australian Collections

Art Gallery of South Australia

6 March to 31 May 2009

There is too a particular movement in these stories as they recur; the arcing curve of chaos to order, the cycle of the seasons, the particular rhythms of life, of theatre, love and war and the shifting balance between good and evil. This form of movement recalls a story arc, a scriptwriting term for the overarching story in episodic story telling that encompasses events, characters, themes and ideas. The best characters and stories keep these arcs alive and moving in the transition of one thing to another; idiot to hero, ignorance to knowledge, peasant to king, order to chaos bonding the whole together in coherence and continuity.

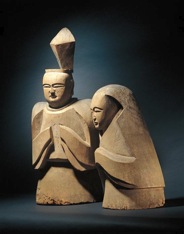

While The Golden Journey presents the collected works within broad groupings of Buddhist Shinto art, Screens and Scrolls and so on, within this the works have been presented so affinities and unities are apparent and stylistic development and changing cultural concerns, including those that are traceable into contemporary Japanese culture and art are clearly discernable.

There is a wealth of objects here including screens, woodblock prints, ceramics, textiles, netsuke and decorative arts and it is as well to remember that any collection sets out the preferences and predilections of the collector, institutional or individual as well as being shaped by cultural influences at the time, in this the Golden Journey sets out a story of these concerns. Seeing The Golden Journey as a set of arcing narratives that run side by side overlapping and enriching each other allows a deep and nuanced picture of Japanese art and culture to emerge as well as a sense of its sustained unity.

The Death of Sakyamuni Buddha (c 1880) is a particularly dense compression of an entire story in a single frame. The scroll is dominated by the golden figure of the Buddha, around him are the golden bodhisattvas, heavenly gods and others, titans and ogres, the whole foreground of the scroll is packed with sorrowful animals, real and mythical, a grieving white elephant, a monkey holding its paw to its head, ox, beaver, camel, frog, dog and phoenix, mourning and rendered with an affectionate humour they are all here and immensely appealing drawer the viewer into the religious lessons the scroll was designed to give. There’s a richness and density to this image that acts like a story generator loosing all these narratives into religious lessons, it’s humour and aesthetic appeal integrating it into life. For this is art that is continuous with life, that speaks to and from knowledge that the viewer has, it acts as a repository and ensures its continuing relevance to culture.

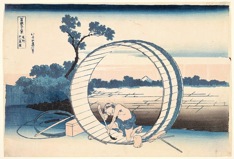

The two large panelled screens Battle Scenes from the Tale of Heike (early 17th Century) depict scenes from the martial 13th century tale of the Taira and Minamoto clans in the Genpei War. On these screens the warriors sweep down dynamically and across in swathes dividing the plane and exploiting the ability of the folding screen to suggest distance, depth and movement. The overall impression is bedazzling with the surging force, the restrained colour of the figures against the bold background of flat gold and stylised landscape and the incredible detail, detail that would have allowed viewers to identify characters and scenes. The narrative moves across and curves up the screens in an almost cinematic progression, and the end effect is of watching the tale unfold as if through time. The triptych woodcut The Night Attack on Kumasaka at Akasaka, Mino(1860) seems to be a clear forerunner of manga concerns and conventions with its graphic clarity, dynamic action and the dazzling shaft of light that cuts an illuminated wedge across the central portion of the images as the almost superhuman hero fights off the attacking hordes. The woodcut, The priest Raigo of Miidera transformed by wicked thoughts into a rat (1902) also has manga’s love of the dark grotesque with the group of rats whirling above the deformed priests head.

The dynamic visual narratives employed in the Genji and Hieke screens, the repetition of visual forms and these arcing narratives through these and other works provide both an overarching continuity of theme and form and a vivid animation. A sense that these are stories that are still being lived out connects these almost mythical narratives to the lives of those seeing them. These are stories and forms that continue to resonate through Japanese culture, manga mobilises these visual forms and myths, samurai dramas are still made.

The stories that can be followed through the wealth of beauty seen in The Golden Journeyencompass whole worlds of thought, imagery and history, they reach backwards and forwards in time to reveal and delight.

Jemima Kemp

Published

April-May 2009

Comments (0)