BLAST THEORY

Rider Spoke

around Adelaide, 20 to 22 February 2009

LYNETTE WALLWORTH

Duality of Light

Samstag Museum, 19 February to 24 April 2009

DENNIS OPPENHEIM

Performance Films 1970 – 74

Art Gallery of South Australia, 7 February to 29 March 2009

RICHARD BELL

Scratch an Aussie

CACSA, 13 February to 22 March 2009

And I do. It’s something I’ve never spoken aloud before and I tell this voice, in the mic, in my doorway, in the dark city, about my secret. This is Rider Spoke.

Conceived by the UK performance group, Blast Theory, Rider Spoke is an event of cycling, listening and recording. An urban tour of discovery and exploration, both physical and psychological. Cyclists are equipped with a GPS console (Nokia 810 with flock of swallows) earbuds and mic, the GPS tells me where I can hide to record and finds the stories of others who have passed this way for me to listen to. The voice asks me questions and my answers pass into the memory bank for other riders to discover. The voice simply asks me what I want to do and the GPS does the rest cleverly, ethereally weaving an aural map of the city and its citizens.

The questions are intimate “tell me about the last time you held someone’s hand in public and what it felt like” ” tonight say your promise out loud to the air”. It should feel exposed but that intimate voice and the curious no time of travel, where suspended between place and state we might be anyone, makes it allright to tell my secrets. And it seems we all do, the stories are authentic, personal, painful, shared secrets that dissolve time, space, the divisions between us and knit us travellers together. Locked into the event we become riders, writers and readers making and unlocking the invisible texts inscribed on the city.

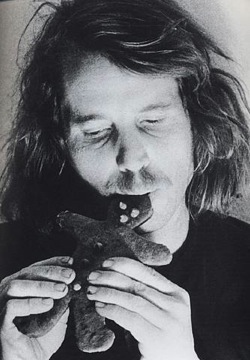

Images courtesy The British Council

Travelling differently, Dennis Oppenheim spent the early ’70’s filing, crushing and nibbling away at these same boundaries of self and world. In Fusion- Tooth and Nail (1970) he paints his teeth with red nail polish to match his fingernails in an attempt to bond the two together. The end mess of nail polish mixed with sticky spit only serves to make evident the impossibility of this and the immutable boundaries of the body. Likewise, his attempts to make his hand disappear in Disappear (1972) by flapping it about rapidly in front of the camera while chanting “I want this part of me to leave, to go” points to the persistence of flesh and the instability of perceptual knowledge. As even when his hand does disappear briefly from sight, we know that it still exists.

The seeming sheer pointlessness of all this activity, Oppenheim crushes ferns and has rocks dropped on his stomach, is precisely the point. His work embodies ideas of duration and endurance in form and intent and is only really understandable in these terms. This relentless input and output points concisely to the structures of time, narrative and knowledge, the endurance of the body and the seemingly inerasable divisions between it and the world. However hard Oppenheim tries he can’t process his body out of the world or bond it to it.

Wallworth’s work pulls us into places of profound self confrontation, peeling away our public skins. In Duality Of Light (2009) a spectral image in a seemingly boundless dark space becomes a revenant of self. Unadorned, we’re brought to a realisation that we are just one creature amongst many. Hold: Vessel 1 & 2 (2001-7) is an immersive space of wonderment and a call for an expanded idea of humanity in which the natural world is not merely instrumental or exploitable.

Librado Romero/The New York Times

As Wallworth’s work skins us ever so gently, Richard Bell’s Scratch an Aussie (2008) abrades, undoubtedly leaving some viewers itchy and uncomfortable. Annexing the privileged space of the therapist’s couch, Bell sets up as psychologist to a range of blue eyed, blonde, physically perfect and slightly thick Aussies, all in gold swimwear. A client expresses her outrage at the theft of her handbag, her disbelief that the thieves thought it was alright to come into her house and just take it, blissfully unaware of any irony in recounting this story of petty dispossession to an Indigenous man.

Lynette Wallworth, Hold: Vessel 1, 2001

photograph by Colin Davison

Bell resorts to word association to deconstruct his client’s (and Australia’s) psyche, “genocide” gets nothing, “dirty” gets “Aboriginal” and his self satisfied clients gleefully embark on a series of racist jokes and epithets. Yet Bell, by resolutely refusing to take a moral position himself doesn’t allow the viewer to get up a good head of righteous outrage. From a fluffy white cloud like bed, he confesses to his therapist, that while he pities his clients he doesn’t want to save them, he just wants to keep taking their money and he’s cracking up at the jokes. Scratch an Aussie is as much about the attitudes that define indigenous people as necessarily victims as the stereotypes that underpin the jokes.

Fitting with Bell’s unrepentant political incorrectness is the beautiful irony of his appearance at the Sydney Biennale. Scratch an Aussie scored one of the best venues on Cockatoo Island, the Wardens Cottage complete with polished floors and comfy lounge, overlooking what was once a white mans prison.

See more of Blast Theory atwww.blasttheory.co.uk and on youtube

Published March 2009

Comments (0)