In Heidi Kenyon’s evocative installations things have been, in her words, messed with. Her arrays of objects have been shifted, skewed, undone, disrupted, unravelled and altered. Still recognisable and bearing the marks of previous incarnations, they are quite indubitably not what they once were.

Kenyon deploys her materials as a director utilises cinematic effects and her installations, whether discrete groupings in gallery settings or immersive site-specific environments become stages on which enigmatic narratives are enacted. These poised alliances of objects inhabit their spaces with anima and chutzpah and seem on the verge of speech or temporarily stilled from some ceaseless activity. In work seen at CACSA this year, a group of battered school chairs stand caught in dramatic Chekhovian tableau, while in The Air Finds It Hard to Breathe (FELTspace 2009), a grand piano pauses almost sheepishly halfway through a wall. There’s a strong streak of mischief in all this, of worlds shifted to one side. Like fairy tales, these worlds have their own self contained logic where the surreal is normal and things are fundamentally unstable.

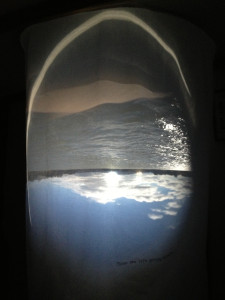

Kenyon’s practice springs from the specific and material but the immaterial: traces, shadows and the invisible relations between things are at the core of her work. These glimpses and intimations are in the cast of a carved leaf, the relations forged between like and unlike things, the light and shadow of the photograph or the live projection of a camera obscura. In Everything You Can Think Of Is True (2007) precisely carved avocado leaves cast shadows of a sleeping child, a bed and wolves in a play of fairy tale archetypes. In it’s second telling (2008), awarded the Constance Gordon Johnston Sculpture Prize, carved leaves again cast their shadows of eyes and faces inside a spiralling forest of unwound vinyl records. Alchemically transformed through copper electroplating, these leaves reappear in Of Things Past (2010) and I’m Still Here (2012) incised with apples, a woman’s face, human fingerprints, set amongst real trees. Vivid yet insubstantial, these ‘disappearing objects’ sit at the edge of perception inviting entry into the work. Kenyon’s use of the camera obscura, (introduced after spending her Ruth Tuck scholarship at the Centre for Alternative Photography, New York) in I’m Still Here and Turn Back to the River (2013) inverts and re-presents the world. Turned upside down, transformed into a live flickering projection and cast back into an interior the world is made entrancingly strange and an invitation to reverie.

Driven by the ‘curious complexity of everyday things’, Kenyon’s process is equally complex. A natural fossicker, she seeks out provisional objects, ones on the cusp of becoming something else or bearing the marks of their histories. Drawn to those objects close to the body and that we physically and psychically inhabit: chairs, boxes, teacups, cassettes, cameras, selected not by form but by the punctum, the point of resonance that each offers. Her process is deeply intuitive, a ‘messing about’ with objects as a kind of materialised wondering and constant ‘what if’ that brings these startling transformations. She unravels, unpicks, undoes and unwinds objects, teasing out their essence, inherent characteristics, and memories.

As things are remade consonances and connections are accentuated and memories liberated; a leaf is engraved with a fingerprint, the relations between human and natural world made apparent, a chair becomes a body. Through this unmaking and remaking her objects are vivified becoming ‘subjects not just materials’, and actors in these tableaus. The transformation of significant objects (a box carved by her great grand uncle, a tobacco tin) into pinhole cameras in Objectified (2012) produced images within domestic items making object and image inseparable as if the object had spontaneously generated images from its own inhering memories.

Time and labour intensive, this process is guided by Kenyon’s commitment to the haptic and the analogue, in her definition any material that can be worked by hand but also in its common understanding as seen in the reiterations of vinyl LP’s, cassette tapes and analogue photographic techniques throughout her work.

These recording technologies are deeply connected to Kenyon’s practice as a form of ‘memory work’[i]. Her concern with memory is not with memory as retrieval but as an act of creation intimately linked to identity, knowledge and as a dynamic recuperation of time. For Kenyon, this creative memory work can be ‘an anchoring space’ in the relentless simultaneity of the informational age and the narratives created a means to explore new forms of knowledge and engagement with the world.

These enigmatic narratives that her installations are engaged in are holey stories, mysterious to the core where each element, material and immaterial is necessary and held in poised relation to every other. The absences are invitations to entry and reverie as objects trigger memory and associations. They are in a way loose knit story machines inveigling viewers to engage with memory as act of dynamic becoming.

Each body of work appears as an organic outgrowth of an evolving, deepening line of thought rather than an end point and shows an increasing refinement and sophistication. Her career to date evidences a self propelling drive and determination with numerous solo shows locally and nationally and group shows in London and Colombia. Kenyon was awarded the Ruth Tuck scholarship (2010), the MF &MH Joyner Scholarship (2012) and the Qantas Foundation Encouragement of Australian Contemporary Art Award (2012).

Recent work has taken a liquid turn with Turn Back to the River (2013), a site-specific project as part of the national One River art program. Railway carriages on the edge of Murray Bridge have become camera obscuras, transforming the town’s daily life into a mesmerising live film. A further carriage, too delicate to enter is filled with postcards close stacked like leaves recording resident’s riverine memories. Watery cast glass ‘phantom limbs’ will repair salvaged chairs for work in progress for a FELTspace group show in October this year and a residency in December will take her to Venice’s Scuola Grafica.

With a sure eye and a story tellers art, Kenyon conjures these shape shifting objects and live spaces where, like all good stories the ending is never certain.

Jemima Kemp 2013

All quotes from the artist in conversation with the writer or from the artist’s writing.

[i] Gibbons, Joan, Contemporary Art and Memory: Images of Recollection and Remembrance 2007

Comments (0)