Bianca Barling, Jane Burton, Monica Tichacek, Mimi Kelly and Pat Brassington.

South Australian School of Art Gallery

17 February to 13 March 2009.

At the heart of the Gothic disorder that moves through the works seen here is female desire. Chaos as the product of women’s loosed desire is the unspeakable secret at Gothic’s core, a force so dangerous that it must be displaced onto things; dresses, fabrics, spaces and it is the conflict between the attractions of desire and the horror of bodily dissolution that underlie its irreconcilable tension between freedom and constriction. These tensions and attractions appear in the displacements of dressing up and acting out, the hair, the patterning and textures of clothes and textiles, the rooms, bodies, organs, ambiguities and diversions, all the desire saturated, slippery imaginings of Dark Dreams and Fluorescent Flesh.

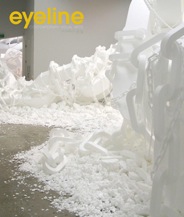

The conflict between desire and dissolution is played out in the tension between interior and exterior and in this intense interiority and claustrophobia, from Monica Tichacek’s satin padded cell and Pat Brassington’s Cambridge Road (2007) series that resemble 1930’s crime scene images, to the tinkling pornographic doll house of Bianca Barling’s Gammelfleisch(2009) that forces the viewer to peek in like a gigantic Alice, this evasion and deflection could be read as an elusive strategy of control.

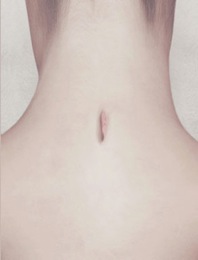

Jane Burton’s work mobilises this tension placing the viewer in the position of unsatisfied voyeur. In The Other Side #2 (2003), the dense patterning of wallpaper, blood red carpet and blinds suggests a muffling constriction and lonely purpose to the woman. Desire and self are displaced into the smothering textiles with no promise of release. There’s no voyeuristic frisson in Burton’s work despite the nudity as the onlooker’s gaze is stopped dead. Seen only in reflection, face obscured under hair, the body in The Other Side becomes a performative vehicle, in the words of another song “she’s not there” or not there to be looked at.

This smothering unease is present too in Monica Tichaceks’s video Lineage of the Divine (2002) where the surgically constructed Amanda Lepore, like a grotesquely exaggerated Andrews sister and the artist are conjoined by an umbilicus of bound blond hair. Inside this soft cell, Lepore seems at ease while the artist, constrained by prosthetic braces on her limbs and curiously passive is kneaded and manipulated by Lepore. All the constructions and constrictions of the made feminine are evident, simultaneously repellent and attractive.

The death in lifeness of hair renders it both uncanny and fetishistic and its recurrence in these works is not accidental. As hair in the Gothic symbolises bodily continence and psychic order, so too do the elaborate upsweeps in Lineage of the Divine and as the unkempt hair of the porn stars inGammelfleisch is a shorthand for sexual freedom, the carefully tousled hair of Mimi Kelly’s would be Varga girl in Untitled #5(2009) offers a curiously neutered come on.

PJ Harvey’s Dress is disrupted and saved by its irruptive chorus, “if you put it on”. Nothing is inevitable, not narrative, not desire and to this end the artists in Dark Dreams and Fluorescent Flesh divert and deploy, disrupting and constructing exits from these soft cells of desire.

Comments (0)