Celebrations of the grotesque; the new sublime in Australian contemporary practice

University of Sydney Art Gallery 17th August to 12th October 2008

Ben Cauchi, Julia de Ville, Sharon Goodwin, Pete Volich, Emma van Leest, Starlie Gekie and Liyen Chong

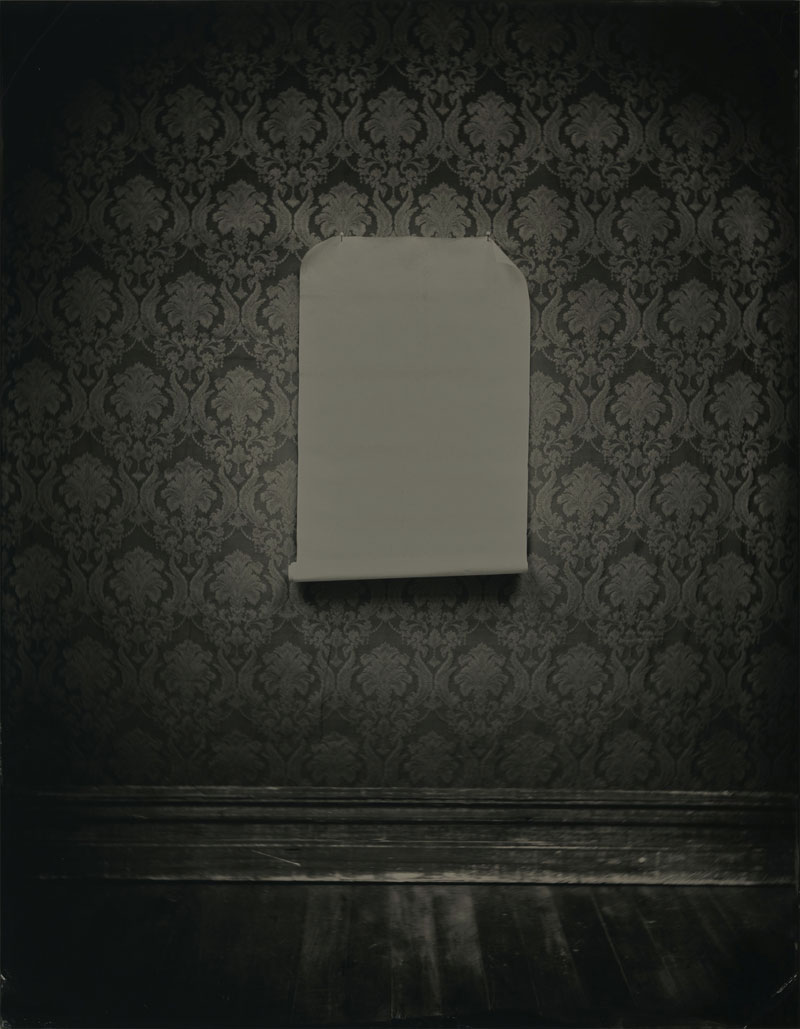

Ben Cauchi ‘Dead Time’, 2007, Ambrotype, 43 x 36cm

Image © The Artist

The engine at the core of Victorian culture resembles its own science fiction, an impossibility drive, powered by the friction of the irreconcilable contradictions between all its cultural forms, social strata, ideas, beliefs and realities. Working in and between this multiplicity of cultural forms and voices, the artists in New Victorians engage with the grotesque, death and life, otherness and identity.

While all this sounds messy, the works shown in the elegant space of the University art gallery are exemplars of decorum. Finely made, modestly sized and with few of the works breaking out of the containment of box or frame, this feels like a very quiet, well behaved exhibition. Yet up close these works speak, obliquely, cunningly and subversively of those things normally unutterable in Victorian speech.

Liyen Chong embroiders her own hair into small, exquisite canvases of skeletal figures and frames resembling book title pages of the kind that held moral aphorisms. A traditional Chinese craft, this technique recalls Victorian commemorative hair jewellery and the fetishisation of women’s hair as a substitute for their sexuality. Hair held and stitched down produces a feeling of visceral unease but the skeletons are slyly comic and the Oriental dragon sporting almost unnoticed in the curlicued border of Verso, possible means ending hints at other truths outside of the frame.

Shadowy identities move through Emma van Leest’s miniature dramas of the exotic. Constructed of paper cuts stepped back inside a glass display box the effect is of looking through an elaborate stage set or a series of Indian screens. Saffron orange and sprinkled with glitter, they embody the lure of the exotic other that India held for the Victorians. Within there is a complicated game of hide and seek amongst the grand architecture, the Indian gods and goddesses are rendered in full detail, are alive and desiring while the simple silhouettes of the Victorian women wander apart and isolated suggesting that it is really they who are other.

Starlie Geikies fine pencil drawings of romance novel titles, So Wicked My Scandalous Desire, The Saddest Scruples, are speech acts of desire and possibility. Drawing on the popular sensation novels of the 1860’s that articulated women’s frustrations, these quietly offer the glamour of transgression and all the attraction of transformation, the softness of the lead lending them a particularly intimate voice.

Pete Volich’s photographs document the detritus on Hackney Marsh in London and while the digital quality of the prints is somewhat discordant with the seamless finish of older processes seen here, their recording of the things left behind is sometimes unsettlingly intimate. The unknown story of each object evokes the unfixed nature of the site itself, refuge for the solitary, home for the group at a point before it is irrevocably transformed. The idea that, with evolution that any forms might be possible is contained in the loose irruptive energy of Sharon Goodwin’s Enlightenment Now. Painted to resemble 19th century woodcuts and illustrations it sprawls on the floor a fantastic, grotesque hybrid combining the classical, mechanical and medical.

Ben Cauchi’s ambrotypes and tintypes use the imagery of spirit photography, Dead Time (ambrotype) depicts a glowing orb against an ornate wallpapered wall, its undeniable presence asks for belief yet it reveals no secrets in return. The Ambrotype process produces a unique glass negative that mounted against black is viewed as positive, the reversal of positive/negative in the ambrotype embodies the relationship between the spirit and real worlds existence side by side. Their soft deep tones, lack of contrast and the depth afforded by viewing through glass make these images profoundly still and deeply mysterious, demanding contemplation. Cauchi’s images exist in a liminal space of suspended time where perception and reality are unfixed and questioned.

As Cauchi’s images depict the occult and the unseen, Julia de Ville’s memento mori jewellery brings the dead back into circulation amongst the living. Not merely reminders that death will come to all, her use of preserved animals combined with gems refers to the Victorians plunder of the natural world for ornamentation and furnishing but affords these creatures a primacy and dignity resisting their reduction to mere ornament. To wear them is an acknowledgment of the value of all life.

This new breed speak above the cultural din and kaleidoscopic colour of the original Victorians with refined voices and forms that elegantly conceal a subversive intent.

Published eyeline 68

Comments (0)